As for training, nothing will ever replace the Spartan/Roman practice of making the training harder than any battle imaginable. Because any army’s allegiance is the foremost indicator of how well it will fight and for whom, recruiting armed forces among one’s own citizens-and on the broadest possible basis-is of paramount importance. But only when ordinary citizens are conversant with the principles of war can they use warriors and not be used by them.

What place should the “art” of war have in any polity? Here, the word “art” means “profession.” Machiavelli’s conclusion is what, in our time, we call “civilian supremacy” over military affairs, lest the military interests divert the polity from its ordinary objectives. What attention, after all, should we pay to comparisons between short and long swords and spears? Readers interested in warfare’s timeless principles, however, will be rewarded by spending time with a first-rate mind as it considers them. The modern reader may be put off by how closely the discussion tracks the weapons and tactics of a time when gunpowder was just beginning to affect Western warfare. Although the expert, Fabrizio, is obviously Machiavelli himself, the format provides at least an arguable degree of separation between Machiavelli and his advice.

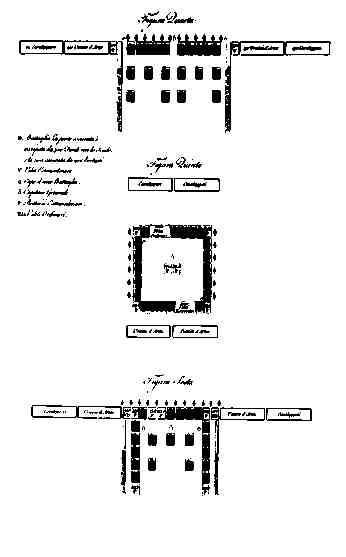

Its format is that of a conversation between a military expert and interested citizens. The book is wholly practical, considers contrasting arguments, and even includes illustrative diagrams. The Art of War’s clear, and concise style is diametrically opposed to that of The Prince. In this, the least known of his works, Machiavelli gives straightforward advice on organizing and conducting military operations.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)